“Knowledge is power”

Francis Bacon

InvestSense, LLC, is a research and educational company whose mission is to provide information to help investors, investment fiduciaries, and organizations better understand that the investing does not have to be complicated, confiusing or intimidating. InvestSense believes in the message of our byline – “The Power of the Informed Investor.” InvestSense is dedicated to providing information that investors can use to privately and easily assess any investment advice provided by financial professionsals

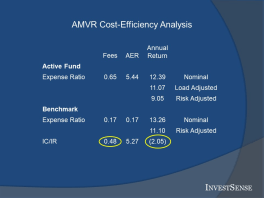

The cornerstone of InvestSense’s program is the Active Management Value RatioTM (AMVR). The AMVR is based on the research and experience of recognized leaders in the investment and financial services industry. The AMVR is essentially the well-known cost-benefit equation, with the input data being based on meaningful modifications of everyday cost and performance figures that are available online. One person described the AMVR as “simple third-grade math….but very persuasive third-grade math.”

Thomas Jefferspon once said “knowledge is power, knowledge is safety, knowledge is happiness.” Hopefully, the content provided in our “Blog” and “The InvestSense Challenge” here will help you achieve each of the goals Jefferson enumerated.