In a recent Wall Street Journal article, Jason Zweig discussed the lack of transparency with regard to financial advisers.1 While I agree with his assessment, I believe that he may have actually underestimated the damage resulting from such lack of transparency.

The financial services industry usually restricts their mutual fund investment recommendations to the overpriced and consistently underperforming funds of their broker-dealer’s “preferred providers.” Many investors are totally unaware of this system, which is designed to benefit the brokers/financial advisers and their broker-dealers at the expense of the investors.

Mutual funds pay some sort of financial consideration in order to gain access to a broker-dealer’s brokers. The regulatory bodies who are charged with protecting public investors, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Investment Regulatory Association (Finra), actually condone such programs.

As proof, one needs look no further than the SEC’s recently enacted regulation, Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI)2. While promoted as requiring that brokers/financial advisers always put the best interests of their customers first, a little-known loophole, the “readily available alternatives” language, actually allows brokers/financial advisers to limit their recommendations to the aforementioned cost-inefficient products of their broker-dealer’s “preferred providers.

As a former securities compliance director overseeing both general stockbrokers and registered investment advisers (RIAs), I believe that such programs and regulations violate both the letter and the spirit of applicable securities law, protecting Wall Street’s interests rather those of public investors.

InvestSense submitted the following public comment during the consideration period on Reg BI:

While I appreciate the fact that the SEC recognizes the need to address the fiduciary issue, I have concerns about whether the SEC is sincere about adopting a meaningful fiduciary standard that will provide the protection that investors need, or just putting on a show that will result in a watered-down version of FINRA’s “suitability” standard.

The SEC’s mission statement clearly indicates that protection of investors is a primary purpose. Judicial decisions involving the agency have clearly stated that it is the SEC’s duty to protect investors, not the investment industry.

In Norris & Hirshberg v. SEC (177 F.2d 228), the court rejected the defendant’s suggestion that the securities laws were intended to protect the investment industry, stating that

“[t]o accept it would be to adopt the fallacious theory that Congress enacted existing securities legislation for the protection of the broker-dealer rather than for the protection of the public. On the contrary, it has long been recognized by the federal courts that the investing and usually naive public need special protection in this specialized field.” (at 233)

In Archer v. SEC (133 F.2d 795), the court echoed those same concerns, stating that

“[t]he business of trading in securities is one in which opportunities for dishonesty are of constant recurrence and ever present….The Congress has seen fit to regulate this business.”

Any suggestion that a “suitability,” or “just OK,” standard provides the same protection that a true fiduciary, or “best interest at all times,” standard is disingenuous and a blatant violation of the agency’s mission statement and the very purpose for which the agency was formed.

The need for a meaningful fiduciary standard for anyone financial services to the public can also be seen in the investment firms retreating from being held to any fiduciary duties in connection with 401(k) plans, arguably in order to engage in the same abusive marketing strategies that led to the DOL’s fiduciary standard in the first place.

In FINRA Regulatory Notice 12-25, FINRA stated that the suitability standard and the best interest standard are “inextricably intertwined.” If one accepts that as true, then the SEC should have no objection to clearly defining the legal duty owed to investors as a “fiduciary” duty and defining the duty using the term fiduciary and the terms set out in the ’40 Act, since the best interest standard requires a higher standard of conduct(fiduciary)than the suitability standard just OK).

The late General Norman Schwarzkopf once stated that “the truth is, we all know the right thing to do. The hard part is doing it.” For the sake of American investors, follow the court’s admonition in Norris & Hirshberg and do the right thing and properly protect American investors, instead of the investment industry. by adopting a meaningful fiduciary standard.

As expected, the SEC totally disregarded my comments and enacted Reg BI with the “readily available alternatives” loophole. To be fair, Reg BI may actually provide much needed investor protection in some cases. However, in my opinion, the “reasonably available alternatives” loophole totally destroys any hope of investor protection with regard to the quality of advice issue.

The Active Management Value RatioTM

Recognizing both the shortcomings of Reg BI and the investors’ need for investor protection, I created a simple metric, the Active Management Value RatioTM (AMVR), which allows investors to quickly and easily evaluate the prudence of actively managed mutual funds relative to comparable index funds. The AMVR is based primarily on the groundbreaking concepts of investment icons such as Nobel laureate Dr. William F. Sharpe and Charles D, Ellis.

Sharpe helped establish the general framework of mutual fund analysis, stating that

Properly measured, the average actively managed dollar must underperform the average passively managed dollar, net of costs…. The best way to measure a manager’s performance is to compare his or her return with that of a comparable passive alternative.3

Ellis then contributed the concept of comparing incremental cost versus incremental returns, stating that

So, the incremental fees for an actively managed mutual fund relative to its incremental returns should always be compared to the fees for a comparable index fund relative to its returns. When you do this, you’ll quickly see that that the incremental fees for active management are really, really high—on average, over 100% of incremental returns.4

One of the benefits of the AMVR is the simplicity in interpreting the metric’s results. In analyzing an AMVR analysis, the user only needs to answer two simple questions:

(1) Did the actively managed fund provide a positive incremental return?

(2) If so, did actively managed fund’s positive incremental return exceed the fund’s incremental costs.

If the answer to either of these questions is “no,” then, under the Restatement’s standards, the actively managed fund is imprudent relative to the benchmark index fund.

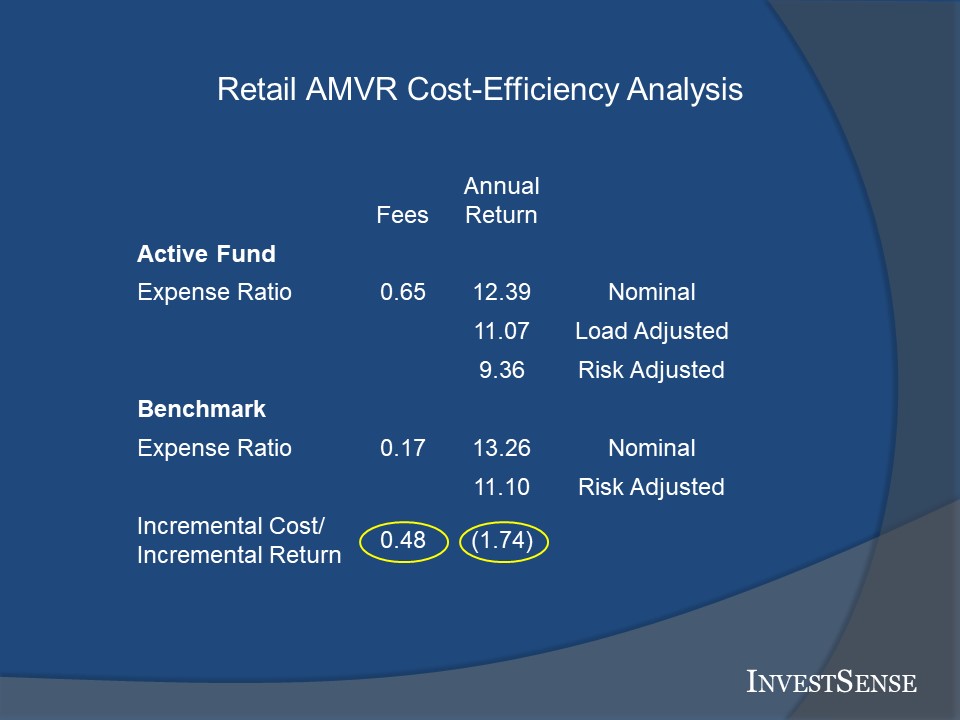

Here, the AMVR analysis is of a actively managed mutual fund from a fund family that brokers/financial advisers often recommend due to the high commissions available to them. However, using the publicly reported, or nominal, returns, the actively managed fund would be an imprudent investment relative to the comparable index fund since the active fund had incremental costs of 48 basis points and failed to provide any positive incremental return. Any investment whose costs exceed its returns is obviously not a wise investment choice.

“Basis points” is a common term used in the financial services industry. Technically, it is 1/100th of 1 percent (0.01). To simplify the AMVR cost/benefit analysis for investors, I often suggest that they “monetize” the cost by simply thinking in terms of dollars instead of basis points. Here. the question would be whether an investor would be willing to pay $48 in order to receive $13 in return. Obviously not.

The problem with nominal returns is that they are often misleading, as they do not consider important factors such as risk assumed and the implicit costs due to the correlation of returns between comparable investments.

Load-Adjusted Returns

Unlike most index funds, actively managed funds often charge investors a “front-end load,” a fancy term for the commissions actively managed funds pay brokers/financial advisers for selling their funds. The amount of the front-end load is immediately deducted from an investor’s initial investment in the fund, effectively reducing the investor’s actual investment. As a result, even if the actively managed fund achieved the same return as the index fund, the investor in the active fund will receive less.

This reduction in return is often overlooked, but should not be. Since the overwhelming evidence is that actively managed are cost-inefficient, with most of them not even being able to cover their costs, this lag in returns is likely to continue over time.

Studies have shown that even relatively minor costs and losses can dramatically impact an investor’s end-return. The General Accounting Office has estimated that over a twenty-year period, each additional 1 percent in costs/losses (100 basis points) reduces an investor’s end-return by approximately 17 percent,5 Combining the incremental cost and incremental loss in the example above, the 219 loss in basis points would result in a loss of more than one- third of an investor’s end-return.

Risk-Adjusted Returns

Another factor that investors need to consider is the impact of risk on their investment returns. A common saying is that returns are a factor of risk. A basic concept of prudent investing is that an investor has a right to receive a commensurate return for the additional costs and risks inherent in an investment. Again, more often than not, actively managed funds do not provide that commensurate return.

Here, the actively managed fund actually has a slightly lower level of risk. As a result, the actively managed fund’s performance relative to the comparable index improves, reducing the amount of its incremental cost. However, the actively managed fund still underperforms the index fund and is still cost-inefficient relative to the index fund, especially when incremental costs is considered.

Some investors avoid addressing risk-related returns due to the calculations involved. The calcualtions are actually quite simple. However, several online sites offer risk-adjusted return data, including marketwatch.com.

Correlation-Adjusted Costs

The next step is to determine if the actively managed fund in our AMVR analysis provides a commensurate return relative to the active fund’s incremental costs. The analysis indicates that the active fund charges an incremental cost of 48 basis points; yet provides no benefit to an investor in the actively managed fund that to offset such incremental costs.

While that scenario is troubling enough, does it actually indicate the full extent of the active fund’s cost impact relative to the index fund? The risk-adjusted AMVR chart shows that an investor essentially gets a similar return for just 17 basis points and avoid the incremental cost of 48 basis point. As John Bogle explained, an investor gets to keep what they do not pay for, in this case an additional 69 basis points in the return.

But does that simple calculation accurately express the full extent of the impact of the actively managed fund with regard to the fiduciary prudence of the active fund? Ross Miller’s Active Expense Ratio (AER) suggests that the cost-inefficiency of many actively managed funds may be even worse than appears at first glance.

Miller’s research suggests that the effective expense ratio of many actively managed funds is often understated by as much as 300-400 percent, sometimes even more. Miller explained the importance of the Active Expense Ratio and Active Weight (AW) metrics as follows:

Mutual funds appear to provide investment services for relatively low fees because they bundle passive and active funds management together in a way that understates the true cost of active management. In particular, funds engaging in ‘closet’ or ‘shadow’ indexing charge their investors for active management while providing them with little more than an indexed investment. Even the average mutual fund, which ostensibly provides only active management, will have over 90% of the variance in its returns explained by its benchmark index.7

The AER compares an active fund’s incremental costs to the fund’s correlation of returns to a comparable index fund. In this case, the actively managed fund has a 97 percent correlation to the index fund. Using Miller’s methodology, that would suggest that the actively managed fund is effectively providing only 15 percent in active management. Based on the AER, the investor in the actively managed fund would be paying an implicit/effective expense ratio of 283 basis points, resulting in an incremental cost of 266 points. Using our previous monetization example, a smart investor would not pay $266 to only receive $17 in return?

Going Forward

While we have gone through the various levels of AMVR analysis, the good news for investors is that in most cases, the cost-inefficiency is exposed by just a simple AMVR analysis based on the incremental costs and incremental returns based on the actively managed and index funds’ nominal numbers.

The basic AMVR requires nothing more what one judge referred to as “simple third grade math” when an attorney attempted to block me from using the AMVR in a case. Investors who are willing to learn more about the AMVR from other posts on this blog and use the format shown in the examples herein can easily prevent unnecessary investment losses and better protect their financial security.

For those who do use a broker or financial adviser to manage their account, I have recommended that they require the broker/financial adviser to provide them with a quarterly AMVR report for each investment in their portfolio, using exactly the same format as shown herein. Many investors have reported that their broker/financial adviser have agreed to do so with “improvements.”

My experience has been that such “improvements are actually attempts to avoid the transparency Zweig talked about, attempts to hide wrongdoing and/or fiduciary violations. As Justice Brandeis once said, “sunlight is the best disinfectant.”